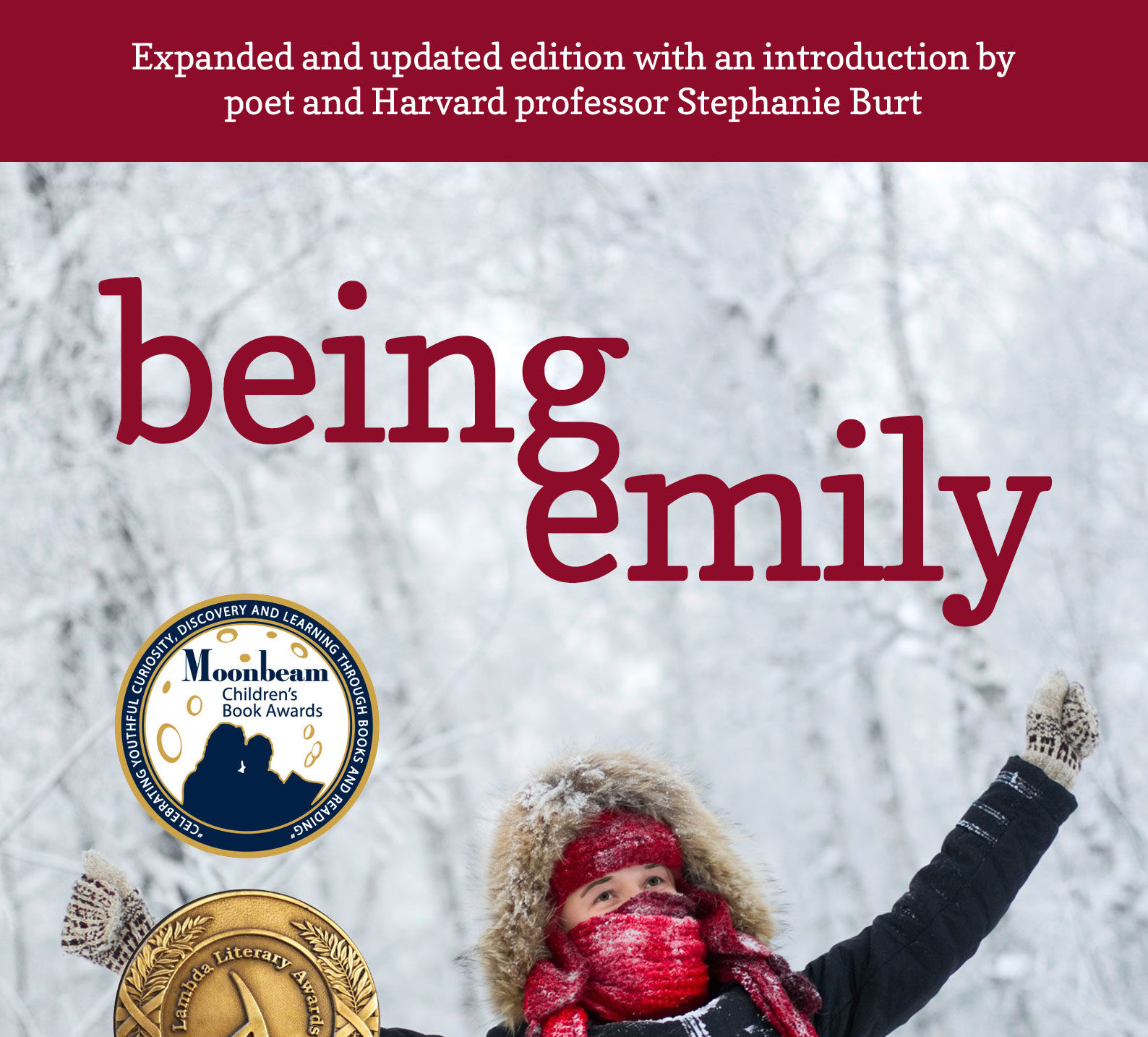

When Being Emily came out in 2012, it was the first YA novel to tell the story of a transgender girl from her perspective. This May, a new edition will be released with updated language and science, new scenes, a new author’s note and an introduction by poet and Harvard professor Stephanie Burt.

To celebrate this upcoming edition, Being Emily author Rachel Gold and Stephanie Burt interviewed each other about the novel and related topics. We begin with questions for both of us and then devolve into Rachel sidetracking Stephanie to talk about comic books. (Which is really easy to do!)

Why is now the time for a new edition of Being Emily?

Rachel: I’ve wanted to change the language in Being Emily for years. For a number of reasons, parts of it were outdated not long after it came out and I learned a lot in the years since its publication. Also it gets taught in Gender Studies courses, so I wanted to update the science to make it even more current. There’s a lot that people still don’t know, so I want this story to be able to do as much as it can for both trans and cis audiences.

Plus early 2017 sucked and I figured trans kids needed all the love we can give them, so I asked my publisher what it would take to re-release Being Emily. That turned out to be a really easy sell. (Thank you, Bella Books!)

Stephanie: a new edition is always a good thing for an important book, so why *not* now? Also, the new edition means new scenes, especially the last scene (the epilogue), which I selfishly want all humans to read. Some non-humans may benefit too. Plus I got to write an introduction, which the first edition did not have!

Rachel: Which is an introduction I want many humans to read!

What’s one of your favorite parts of this new edition?

Rachel: There’s more about Emily’s relationship with her dad—I want to say a bunch about that, but I’ll just end up spoilering people. I didn’t take out anything from the original, but I added scenes that deepen that relationship. Also I changed a lot about Claire’s chapters. I could see better ways to highlight the journey that she goes through. Plus she gets to think and talk about being bisexual more.

Stephanie: Among the other additions, one that’s extraordinarily important to me—and it’s brief—comes when Emily and her dad are learning about the science behind medical transition, from a doctor who’s kind and together enough to explain it.

The new edition explains fertility preservation for trans women starting medical transition. I’m very glad that I’m out and have started transition. I’m also glad that my partner and I have kids. I’d hate for trans teens, or anyone really, to think that you can’t have biological children, if you want them, once you’ve transitioned! You can. But you have to take certain steps first.

Rachel: Also I want to add that I love Stephanie’s introduction, but of course in saying that, I’m going to sound like a cheeseball. The part about it being the first YA novel, “…with a trans girl’s voice at its center, the first one you could give a trans girl and feel good about the idea that she’ll see herself in it.” That’s exactly what I wanted it to be, but had never articulated it that clearly.

Stephanie:

What do we want the next generation of trans kids to know?

Rachel: You don’t have to have it all figured out and you can trust yourself. And there are a lot of ways to be trans. I keep reading amazing posts from people on their blogs or tumblr talking about their experiences of being embodied—there’s so much diversity and wonder! Being Emily a very specific book about one girl’s experience, it’s not the definitive text on how to be a trans girl or a trans person. If it speaks to your experience, wonderful! If it doesn’t, keep reading and if you write, keep writing!

Stephanie: Again, you’ve said the most important things!

The first time I tried to come out as trans, in the early 1990s, what I should have heard from my cis friends—and did not hear, or wasn’t ready to hear (TBH at least one of them tried to tell me), was: FIND YOUR PEOPLE. If you don’t already have friends who have your back, and who have your interests at heart, and who can teach you what you need to know, or work with you to discover those things together, then you need a way to find those friends. And now, in 2018, there are lots of ways. Online communities organized around being trans; online communities organized around something else; in-person meetups and conventions; trans-friendly subcultures of many sorts; Twitter… I tried to say as much in my introduction, and of course the book says so itself. Every Emily needs a Natalie. Ideally more than one.

Corollary the first to the above: YOUR PEOPLE ARE OUT THERE. If you think nobody understands you right now, you may be right (for now), but that’s likely to change, especially if you make some effort to change it.

Corollary the second: your straight or cis or longstanding allies, including your birth family, may well stick by you; you do not necessarily have to abandon them, or expect them to abandon you, in order to figure out who you are. (That’s part of Claire’s arc, but also part of the now stronger arc with Emily’s dad.) Individual straight cis people are not the enemy, and will not necessarily stare at you in blank incomprehension! Sometimes they’ll take a while to understand, but will, nonetheless, eventually understand.

That said, the systems of patriarchy and domination, and the unacknowledged assumptions that go with those systems—from what a man is, to what a woman is, to what sex is supposed to be and why sex matters…. Those systems are, actually, the enemy. The more of us come out, the more of us say what we think, the more of us write about what we think, the more we will be able to understand those systems and dismantle them, or at least get them out of the way, so that we can build something at least a bit better (whether or not what we build looks like the old systems from the outside).

Rachel: And that’s why you’re in charge of saying the things that aren’t stories, because you just put that so much better than I would have, and I wholeheartedly agree.

What do we want the next generation of trans kids to teach us?

Rachel: How to dress. Also how many things don’t have to be a big deal. I’m always impressed when I see young people breezing by things that seemed so hard when I was a teen. Like how we’re so far beyond coming out about your sexuality in some areas that it’s not even “coming out” anymore—it’s either just being or “bringing in.” That doesn’t mean it’s easy for most people, but I think seeing moments of ease helps all of us have more confidence and hope.

Oh and this isn’t exactly teaching (but is), would some of you please program video games with nonbinary characters? I really want to play them! I know some exist, but more and bigger, please!

Stephanie: (deep breath) I’m still learning. It would be a cop-out to say “surprise me; I don’t know what I don’t know.” Wouldn’t it?

I’m older than almost all the other trans people I know, and when I see people younger than me coming out and learning how to be out and describing their lives, my reaction is sometimes “I want to be there to help you” (that is my chief reaction when they are my students). Sometimes, though (when they are not my students), my reaction is “you get to be who you are! Hurrah! I’m happy to stand on the sidelines while you inhabit your awesome world. Thanks for letting me stick around. Please show me—even if you cannot tell me—what you’ve figured out.”

Also, how to dress.

We’re both a little more out than we were a few years ago, how’s that going?

Rachel: [hides behind Stephanie]

Stephanie: [hides behind Rachel] I read BE1.0 when I had just come out for the third time, as publicly nonbinary but privately thinking “maybe I’m really a girl and I should just be a girl all the time and start medical transition.” And I recognized myself so completely in Emily, who was, also, starting to come out.

I’m now pretty much all the way through the social and emotional coming out process, although of course I’m still learning how to do makeup (it’s hard! But parts of are fun, if you are me!) and the legal/financial name change stuff is a ridiculous time suck. I did the whole social and medical transition thing (starting hormones, presenting myself as a woman full-time, using Stephanie all the time as my name and rejecting my guy name) in 2017. None of the things I most feared about doing an honest-to-Artemis social and medical transition—that I’d become a worse parent; that I’d become a worse or less honest partner; that I’d regret what my transition did to my parents; that our kids’ school community would reject me; that I’d become a worse teacher—none of those things happened. My life is better in literally every way.

But it’s still scary. I’m still very afraid of being too open, revealing other people’s secrets, offending people I should not offend, crossing lines and making mistakes. That fear is, also, part of being me.

Rachel: It’s been delightful seeing you come out more. And me too except that I mostly haven’t settled on what to call myself. I keep wanting to give lists or complicated charts, which I think is part of being genderfluid or gender malleable or a nonbinary lesbian. I like that there isn’t a handy box for me to be inside of. I don’t like the boxes, but it makes being out and talking about things a little harder, at least for me right now. And I appreciate that you, and a lot of people, have created space for me to be in a process and not at a destination—and that there may be no destination.

For Rachel: You’ve made some additions and changes between BE1.0 and BE2.0. Is there one big, or biggest, change, or just a stack of small ones?

Rachel: In the first two-thirds of the novel it’s mostly small changes. The language has changed. There are mentions of nonbinary trans people and we briefly meet one! There’s more understanding that not all trans women want surgery, that not all trans women fit the “I knew really young” narrative.

In the last third, I added about four major scenes, including deleting an entire Claire chapter and replacing it. Honestly, I’m a better writer than I was seven years ago (since most of the editing of Being Emily happened in 2010-2011). I got a little mad at myself in the editing process because I could see what I’d been trying to do, but reading it now, it didn’t work. Writers grow and learn; we’re not perfect out of the gate. I’m really glad to have this opportunity to take a story that I love and make it better.

For Stephanie: We both grew up reading comic books. (Now Kitty Pryde is leading the X-Men!) Why is it important to have both metaphors for how you are in the world (“I’m like Kitty”) and to have real-world how-to advice like the kinds in Being Emily (“I’m a trans girl; here are things I can do”)?

Stephanie: That’s a great question! Metaphors and fictional worlds, especially nonrealist fictional worlds (superhero comics, science fiction and fantasy, myths, games), show us possibilities for being and doing that haven’t been realized, or haven’t been realized yet, or couldn’t be realized literally in the real present-day world, even if what they represent emotionally could be realized here and now. They show us that the future can be different from, and better than, the present.

They also let us escape from the here and now, from the constraints and the pressure of having to be the same person all day long (a pressure which, so I’m told, gets to cis people too). And they’re fun! If you identify with X-Men characters, for example, you have to think about problems that in the real world you should be very glad not to have (being infected with Brood embryos, for example) but you also get to make things explode, or become invulnerable, or walk through walls.

If you have only metaphors and nonrealist models for your own experience, though, you won’t be able to make the connections you need to make to your real life, to answer the literal question “what should I do next?” Some kinds of psychological interactions—especially those that involve very long-term relationships, or birth family who are not entirely hostile, or money—are usually better modeled by realist novels (adult-literary or YA) than by science fiction and fantasy. I’d be worse off, and unhappier, without Kitty and Wolverine and Scott and James Tiptree, Jr. and Nnedi Okorafor. But I’d also be worse off, and a worse person morally, if I had never read Middlemarch.

For Stephanie: In BE, after Emily comes out to her parents, her mom goes into her room and takes, among other things, her X-Men comics. Why?

Stephanie: Let me answer that with a series of links:

http://www.xplainthexmen.com/2014/10/kitty-queer-by-sigrid-ellis/

http://www.xplainthexmen.com/2015/04/on-coming-out-queer-identity-and-continuity-in-all-new-x-men-40/

http://www.publicbooks.org/join-mutant-resistance/

https://www.themarysue.com/jay-edidin-tedx-talk-you-are-here/

For Rachel: BE1.0 was almost all alone in the world when it appeared: there were trans people in YA and in adult fiction but not many, and literally none you could recommend to someone vulnerable or young or not yet out (or all three). How much do you think the fiction landscape has changed?

Rachel: I think fiction has changed less than nonfiction, which surprises me. Also I see more changes in speculative fiction than in contemporary. I really want to see more contemporary YA that’s about challenges trans kids face but where those challenges aren’t getting beaten up or your parents freaking out. I’m getting a little hypocritical here because Emily’s parents freak out and in my second book, Just Girls, there’s transphobic violence (against a cisgender character). I know those are real challenges people face, but I feel like we’ve covered that territory enough so let’s move on.

There’s such an opportunity in YA because that’s a time in all our lives when we’re learning about hormones and being adults and embodiment in the context of intimate relationships. I want to see more stories about trans kids learning to have empowering relationships and being joyful in/with their bodies. These stories are out there to be told and they’re more universal than mainstream publishers might think. In YA, everyone is feeling awkward about how to be an intimate/sexual being, but more so if there’s a complicated relationship with how your body is read by others.

That’s not just a problem for trans kids. And there’s starting to be good fiction about cis people deconstructing the gender boxes they’re given. But I think it’s a set of problems that trans kids and authors have more insight about. I’d love to see a novel with a genderfluid protagonist figuring out how to be seen in a relationship when their sense of their body changes day to day. (And yes, if you make me wait long enough to see this, I’ll write it.) I’d love to see more characters who attain whatever aspects of medical transition they want but don’t feel they have to fit completely into female or male boxes. I’d love to see more trans kid protagonists who don’t hate their bodies but hate what the dominant culture insists their bodies mean. And I want to see these told in the subtle, interior ways that make the experiences more universal.

For Stephanie: In your intro you talk about the importance of trans girls being able to see themselves in BE, but also the importance of being seen by others as trans girls. Is there a balancing act to this or do those to aspects reinforce each other?

Stephanie: I’d say there’s a positive feedback loop, at least for me (but I’m pretty other-directed and pretty sensitive to what other people think, especially for somebody in my fields, so YMMV).

The more I think other people can see me the way that I want to be seen, the more I think I can be, or become, or become visible as, the person I want to be, which in this context means: the girl, or the woman, I want to be. (The ambiguity between “girl” and “woman” in there says a lot about who I am, and how I see myself, and I am still figuring out just what it says.)

There is a philosopher I like a lot, Marya Schechtman, who argues that our very sanity, our ability to keep function as souls and minds, depends on our sense that somebody else can see us, and our life stories, in ways that we can recognize as ours.

There’s also a thing that happens when you, or at least when I, read a work of imaginative literature (poetry or novels or comics or anything) and see aspects of ourselves there—the feeling that “this person gets me! This author gets me!” is one of the best feelings in the world, and you can get it from a real live person, or from a book.

Ideally we get it from both. (And then we tell real live people to read that book.)

For Rachel: Emily comes out (sort of) through gaming and gameworlds before she comes out at all in real life (or what we are pleased to call real life). Can you talk about the importance of gaming and gameworlds to trans people, or to LGBTQ+ people more generally, or to you as a writer?

Rachel: In gamewords, you get to try on different bodies and different roles. I think that’s beneficial to a lot of people, not just trans people. But of course it can be especially powerful if you’re walking around in the world and people always treat you one way and then you get to log into this other world and get treated the way you want. I might especially like it because I can have different bodies on different days, which is how I feel in real life too.

Interactive play spaces are great environments for trying out the ways we want to be seen by others and getting feedback. I still remember being a teen, telling a group story with friends, and my character was a werewolf who started as a woman and then turned into a man for a while—and that was a powerful experience for me that I could be someone whose body changes and not just be tolerated, but be valued for that.

For Stephanie: In the novel, Emily’s little brother is always doing these superhero match-up fights, so … Starfire vs. Kitty Pryde, in which they’re both trans? Do they fight, just for fun, or go shopping? If so, where and for what?

Stephanie: They fight briefly, realize they’re not really enemies, and definitely go shopping. Does Starfire have the power to get off Earth whenever she wants, in this continuity? I think not, which means they have to find the nearest awesome mall.

There’s probably a superhero fight going on *in* the mall, because that’s what happens when X-characters go to the mall. I like to think that they stop the fight and then go right on shopping. Assuming it’s time-displaced 1980s Kitty and Starfire, rather than present-day Kitty (whose style has changed!) I’m pretty sure I’ll see them in Sephora, and then at Charlotte Russe.

Rachel: I could not agree more! I was assuming classic 1980s Kitty & Starfire, in which case I think the fight in the mall should be Wolverine vs. anyone and when it’s over, he ends up sitting outside the dressing room holding Kitty & Starfire’s purses and giving shockingly good advice about what looks good on each of them.

Stephanie: I would trust Logan on a lot of things, but I’m not sure I’d trust him on that. But maybe that’s why it’s *shockingly* good?

About Stephanie

Stephanie Burt is an expert in American poetry, both in its composition and its critique. She has been called “one of the most influential poetry critics” of her generation by the New York Times. Burt teaches at Harvard University, sharing with students not only her expertise in poetry, but also LGBTQ literature and graphic novels and comics. She is the author of several texts on poetry, including Close Calls With Nonsense: Reading New Poetry (2009), The Forms of Youth: Twentieth-Century Poetry and Adolescence (2007), and The Poem Is You: Sixty Contemporary American Poems and How to Read Them (2016). Her essays have been featured in a wide range of publications, including the New Yorker, the New York Times, the Los Angeles Times, the Boston Review, and the Times Literary Supplement. She has also published four full-length collections of poetry, among them Belmont (2013), and her latest, Advice from the Lights.

About Rachel

Raised on world mythology, fantasy novels, comic books and magic, Rachel is well suited for her careers in marketing and writing. She is the author of multiple award-winning queer & trans Young Adult novels, including Being Emily (2012), Just Girls (2014), My Year Zero (2015), and Nico & Tucker (2017). As a marketing strategist, Rachel gives presentations and trains professionals on topics ranging from branding to search engine optimization. But if that makes her sound too corporate and stuffy, you should know that Rachel is an all around geek and avid gamer. She also teaches at The Loft Literary Center, including a course that is a roleplaying game. For more information visit: www.rachelgold.com.

[…] If you haven’t read the great interview between me and Stephanie Burt on YA Pride, go read it! […]

[…] Trans Girl Classic Gets New Edition – YA Pride – None of the things I most feared about doing an honest-to-Artemis social and medical transition—that I. myths, games), show us possibilities for being and. […]